Cycling The Brisbane Valley Rail Trail (BVRT)

Words & photos by Bonnie & Dave aka Velo Obscura

Route on RidewithGPS

15 minutes

The Brisbane Valley Rail Trail (BVRT)

At 161 kilometers, The Brisbane Valley Rail Trail (BVRT) is the longest rail trail in Australia. Following the route of the old Brisbane Valley rail line, which ran between Ipswich and Yarraman from 1884 to 1995, the BVRT passes through acres of pastoral land, eucalypt forests, and quaint country towns — with a few seasonal water crossings thrown in for good measure.

The easiest, most popular way to ride the trail is to start in Yarraman and head south to Ipswich, taking advantage of the predominately downhill track. Riding it north is slightly more challenging owing to the uphill grind, but still accessible for all skill levels. Out There Cycling offers shuttle services along the route, and hosts day rides and mountain biking skill sessions. Towns are closely spaced along the route, so food, water, and rest are never an issue. The trail itself is dotted with historical markers, information plaques, sculptures, and trestle bridges. With never a dull moment, there is something for every type of rider on the BVRT.

Having cycled over three-thousand kilometers since April, playing chicken with Commodores and livestock trucks while trying not to careen off the sides of crumbling bitumen shoulders, an escape down a historical rail corridor was more than welcome. Dave and I are not just cyclists, we are curio connoisseurs, oddity experts, pilgrims to the strange and unusual. Our routes are often dictated by bizarre attractions and quirky museums, of which Australia has plenty. For us the BVRT would not only be a reprieve from the Mad Max-meets-Speed level escapades of the highways, byways, and backroads, but an opportunity to visit little-known timber towns, and take in some railway history.

The trail did not disappoint. Excellent trail conditions and interesting features combined with amazingly friendly locals, a trailside urban legend, a ghostly legion of fettlers, Giant Heads, Roy Emerson, and a visit from Australia’s notoriously reclusive Yowie — made for a memorable journey down the BVRT.

Day 1 — Ipswich – Fernvale – Lowood

We started our adventure on the Brisbane Valley Rail Trail outside of Ipswich, at Wulkuraka Station. Built in 1884, the Wulkuraka to Lowood route was the first part of the Brisbane Valley rail line completed. To keep costs low, tracks were laid around rather than through natural features such as hills and gullies, prompting many of its first passengers to describe the winding route as “torturous” and dub it the “serpentine railway”.

The route along the BVRT proved much more pleasant by bicycle, although almost immediately we were faced with a gully crossing. Cement slabs have been installed in most of the gully crossings for a safer alternative to wheeling bikes down and up the steep gravel sides. We passed a few day cyclists going the other way, but for the most part we were alone on the trail, with only the sound of crunching gravel under our tires and birds chirping in the trees.

We stopped in Fernvale for groceries and met another couple long-distance cycle touring, who were heading the same way as us. They told us about the Lowood Show Grounds campsite, and we decided we’d have an early finish for the day and camp there as well. They left ahead of us while we lingered in town to make some lunch, and we caught up with them at camp in the early evening.

Day 2 — Lowood – Harlin

The day got off to a disappointing start with an unfortunate weather forecast: rain expected all afternoon. We pushed on anyway, under a threatening, low-hanging grey sky. Outside of Lowood, we passed the Bicycle Fence, which has become an iconic photo-op on the BVRT, and did some hill climbing, with rewarding views of the Brisbane River.

Our lunch stop was in Esk, a historical timber town. When the Brisbane rail line extended its route to include Esk in 1886, the new transport link allowed both a timber and a dairy industry to flourish in the community, leading to a period of economic growth. The brick colonials and iron lace façades from this era of prosperity still line Esk’s main street. Right as we reached town, the swollen grey clouds unleashed their threat of rain, pummeling everything below in a torrential downpour. We took shelter in a covered picnic area and waited out the worst of it. From that point onward, we had scattered showers for the rest of the day.

Perhaps it was the weather, but we were alone for most of the day. In fact, the only time we weren’t alone was when a trio of horses came across us on the trail. Whether they were wild or not, we weren’t sure, but they showed little interest in us, even as David, the animal whisperer, attempted to call them over.

Shortly before reaching Harlin, we came to the Yimbun Railway Tunnel. Built in 1910, the 100m tunnel is a significant feature on the trail, unique it that it was the only tunnel ever built on the Brisbane rail line. We reached Harlin in the late afternoon and found that the weather had turned Simeon Lord Park into a swamp. Exhausted, we lingered outside the hotel for a bit, discussing what our next move would be. As we were about to leave to rejoin the trail and look for possible undercover areas to camp in, the bartender on duty came outside and told us to come in out of the rain and to wait for the owners, who could possibly work something out with us. Sure enough, when the owners, Jackie and Reese, came back, they set up a canvas tent for us in the hotel’s courtyard, and even offered us the use of a shower.

The Harlin Hotel has a history of helping out stranded individuals during intense rainfall. In 2011, unusually heavy rains caused the Brisbane River to swell beyond its banks, leading other tributaries to rise as well, effectively closing off roads and forcing the evacuation of over 90 rural towns. 40 travelers found themselves stranded in Harlin and were taken in by the publicans of the Harlin Hotel until the flood waters had receded enough for them to safely return home. Although the rain we experienced wasn’t anywhere near as severe, it pounded the roof of our canvas tent all night long like a drum line.

Day 3 — Harlin – Kilcoy – Linville

The previous night’s storm having blown itself out, we were back on the BVRT by 10.00am, and lucky for us the trail was already dried out by the time we started pedaling. Our end destination for the day was Linville, but first we had to make a 54km roundtrip detour along the D’Aguilar Highway to Kilcoy, the Yowie capital of Australia.

NOTE: the D’Aguilar is undulating, pot-holed, extremely busy, and without adequate shoulders. Although we enjoyed the destination, the ride to Kilcoy was not a pleasant experience and we would not recommend cycling the D’Aguilar Highway.

If you are not familiar with the Yowie, he is a member of the Homomythiconicus cryptid family — a long-lost cousin of Canada’s Sasquatch and uncle by marriage to Florida’s Skunk Ape. Yowie sightings have been recorded in Kilcoy and its surrounding bushland since the town’s founding in 1841, but it was a frightening encounter with the elusive beast in 1979 that forever cemented the town’s unique reputation. Teenagers Tony Solano and Warren Christensen were pig-hunting at Sandy Creek, a rural locality just outside of Kilcoy, when they claimed to have crossed paths with the Yowie. The creature was about three meters tall and covered in shaggy brown fur. As it strode into view, the boys found themselves suddenly engulfed in the creature’s horrible, sulfuric scent. They each took a shot at the beast, allegedly hitting it, although their bullets did little to wound the monster and merely sent it running in fear. Or so they thought. As the boys attempted to follow the Yowie’s tracks, they heard the snapping of branches and loud, crunching footsteps behind them. The Yowie had doubled back and was now in pursuit of Solano and Christensen. The boys ran as fast as they could back to the main road, jumped in their ute and sped home.

The encounter made national news and Kilcoy promptly began reinventing itself around the hype, with several businesses adding Yowies to their branding, and the shire council going so far as to rename the town’s green space Yowie Park, unveiling within it a Yowie statue based on Solano’s and Christensen’s physical descriptions of the beast.

The last reported Yowie sighting was in 2007, but it seems everyone in town has seen the creature, even if they’re too afraid to admit it. The woman working at the Kilcoy information centre told me about her own Yowie encounter. Driving home from work one evening, something jumped straight over the front of her ute, its bulk filling up the entire windshield. She didn’t bother to get out and investigate further, just made sure all the doors were locked and the windows up before speeding off. She warned me that the first sign of a Yowie’s presence is its sulfuric stench, which came in handy later that day when we had our very own Yowie encounter. Only instead of sulfur, our Yowie smelled pleasantly of coffee; so pleasant was he that he has joined our cycling adventure! Thanks, Yowie Coffee!

The trail to Linville was exhaustively undulating and hilly. The latter part of the trail became rough double track following the main road, that dipped in and out of gullies and was fraught with drainage issues. We were relieved when we finally arrived and stopped for the day. The BVRT leads right into Linville’s free camp, which sits across the street from the Linville Hotel. The free camp is next to the old Linville Railway Station, which still has its tracks, upon which several restored train carriages sit. The camp is a popular spot for Grey Nomads, and it was particularly busy the night we arrived, likely because the Hotel was hosting live music. We set up our tent on a knoll overlooking the train station, then went to the Hotel for drinks and country music standards.

The Linville Hotel has developed a reputation as the most cyclist friendly hotel on the BVRT. With the purchase of a meal, cyclists get a complimentary hot shower — much preferable to the cold showers in the toilet block at the free camp — just remember to mention that you’re riding the BVRT!

Day 4 — Linville – Blackbutt – Yarraman

The next morning, Linville’s free camp was full of shuttle buses and cycle groups milling about. We passed several group rides, but once again we seemed to be the only ones heading north. The Yarraman to Linville portion of the BVRT is the most popular part of the rail trail, owing to its downhill gradient and the abundance of bigger towns that the route passes through.

Just beyond Linville we came across a memorial plaque to a tragic rail accident that occurred during construction of the Blackbutt extension. On February 25, 1911, a train loaded with ballast crashed through an active building site, killing two men and wounding another. One of the victims, Thomas Love, died instantly and for many years local legend held that his body remained buried under a pile of ballast stones above the rail line. An overgrown path behind the plaque led to this seldom-seen and surreal part of the memorial: a rectangle of ballast stones, surrounded by metal rails, looking exactly like a pioneer grave — perhaps as a nod to Love’s enduring legend.

The men who built and maintained the Brisbane Valley rail line were known as fettlers. Setting up work camps along the tracks, and moving down the line as work progressed, the fettlers lived in tents or, if money permitted such luxury, tin shacks (some of these shacks still stand and can be seen along the BVRT). If fettlers were married, their families often accompanied them, the women taking on domestic duties within the camp. Conditions were harsh, the work back-breaking, the hours long, and death was not uncommon. Many fettlers were fatally injured in work accidents or camp fires; there is even an Australian folk song inspired by the sad life of the fettler:

A strapping young fettler lay dying,

With a shovel supporting his head

The ganger and crew round him crying,

And he let go his pick handle and said…

Wrap me up in a tent or a fly, boys,

And bury me deep below,

Where the trolley and trains won’t molest me,

To show there’s a navvy below.

There’s tea in the battered billy-can,

Place the dog spike out in a row,

And we’ll spike to the next merry meeting,

To show there’s a navvy below.

Hark! There’s the wail of a trolley,

Far, far away it seems clear,

It sounds like the inspector is coming

And hopes to see all of us here.

So, back to your shovels, my boy-lads,

And bed your backs with a will,

This inspector has no time of judgment,

But there’ll be a navvy who will.

A surreal tribute to the thousands of men who worked on the railways suddenly appeared in the dappled sunlight under the gum trees. Rows of couplers sat before a carriage draw bar. Perhaps it was a trick of the light, a dance of the shadows, but suddenly the couplers rose from the sun-scorched earth. Flaking rust, they groaned to life, spirits of long-gone fettlers animating them. The carriage bar became the tyrannical rail inspector, his imposing shadow casting them once more into darkness.

We arrived in Blackbutt in time to visit the Roy Emerson Museum. Roy Emerson is one of Australia’s most famous tennis players, a 28-time Grand Slam title winner who was ranked No. 1 in the world from 1964 to 1965, and again in 1967. Born in Blackbutt in 1936, Emerson was raised on a farm on the outskirts of town, and received his early education —and first discovered his love for tennis — at the Nukku State School, which now houses his museum. Newspaper clippings and photographs of the tennis great paper the walls, and a few of Emerson’s trophies are on display, as well. In 2017, Emerson was in attendance for the unveiling of his statue at the museum, joking to the audience that he was looking forward to the local crows and magpies using it for target practice.

Next to the museum is the old Nukku Siding Railway Station which, coincidentally, was originally located in front of the Emerson family’s homestead. It was moved and restored to its currently location in 2016, and holds a large collection of railway memorabilia.

We’d had a long day on the trail. Museums, tributes, and memorials aplenty — and a surprise water crossing — we were admittedly cycle-fatigued and looking forward to making camp in Yarraman. The town offers an excellent free camp at the BVRT trail head, on the edge of a beautiful pond. After setting up our digs, we cycled into town for a much-needed round of drinks at the Royal Yarraman Hotel. The first face we saw when we got there was … attached to a giant head.

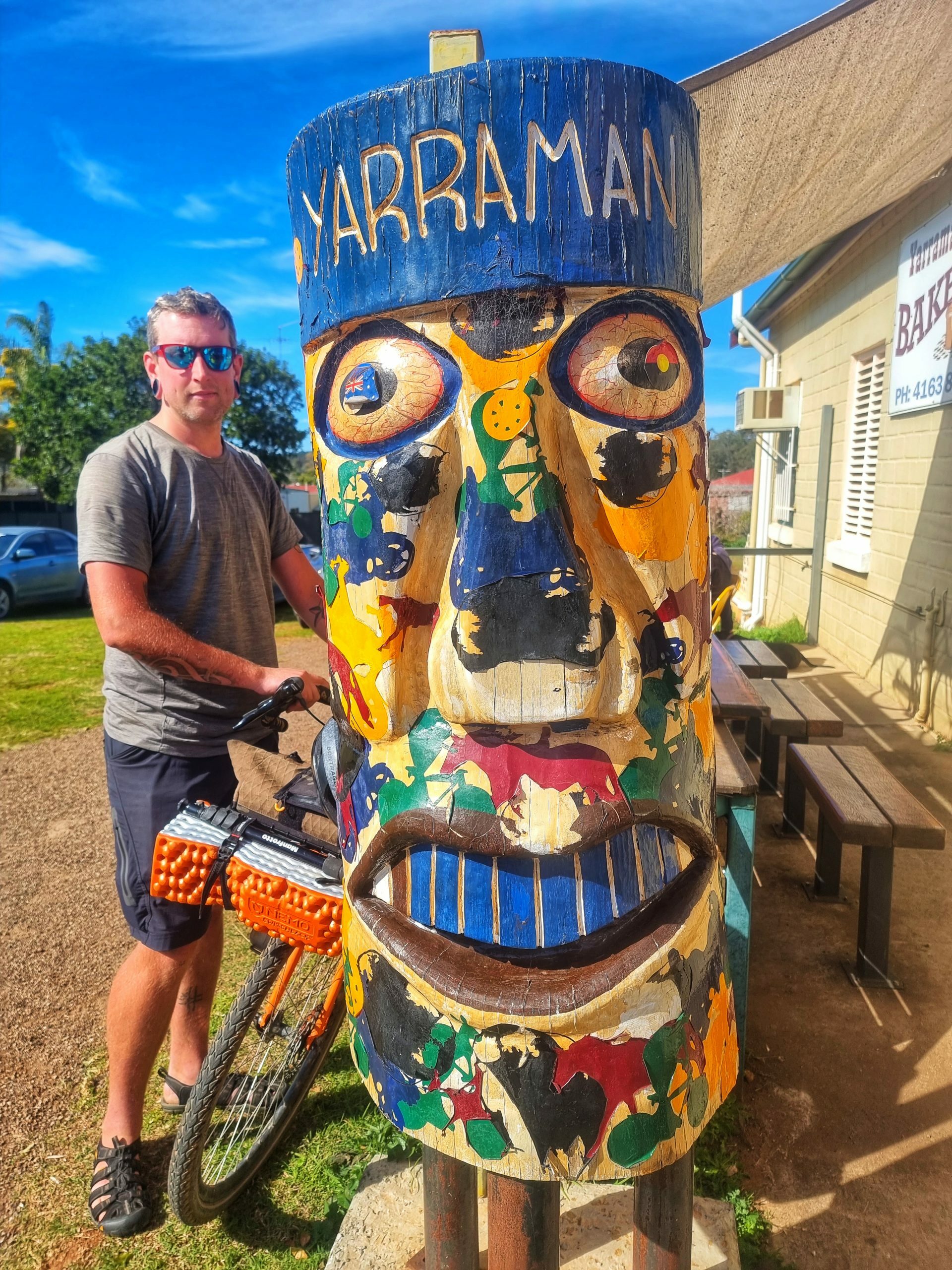

The Yarraman Head is large, hand-carved, with a cheeky countenance. Mystery surrounds him; nobody knows exactly who carved the Head, but legend has it that a group of off-duty Māori tradies carved him out of an old tree stump after a few pints at the Royal. Either way, he has been around for nearly three decades and in recent years local businesses have commissioned their own heads in his honor.

The Kingaroy to Kilkivan Rail Trail (KKRT)

Although we had reached the end of the BVRT, we weren’t quite ready to get back on the highway. Lucky for us, we weren’t far from the Kingaroy to Kilkivan Rail Trail, otherwise known as the KKRT.

NOTES ABOUT THE KKRT:

Although the BVRT ends in Yarraman, you can ride the old Stockman’s Route via Nanango to Kingaroy, the southern terminus of the KKRT. The Stockman’s Route is quite rough, however there is a 2km section that is particularly steep and extremely rocky. The route is rutted and difficult to navigate, with two water crossings. We managed to cycle the route, albeit with some difficulty, on fully loaded touring bikes, but this route would be more enjoyable by mountain bike.

From Kingaroy to Murgon the KKRT is smooth bitumen. From Murgon, however, the trail becomes chunky gravel, is deeply rutted, and has several water crossings. In places it looks like the train tracks were simply removed and the corridor was left as-is, with no grading or resurfacing done whatsoever. We had no choice but to get back on the road at Goomerie, as we had a deadline to meet and the trail was too time-consuming for us.

We would not recommend the northern section of the KKRT for beginner riders or anyone cycle-touring with a heavy load. The trail is rideable, but probably more suited to experienced riders and bikepackers.